Every year for the last few years I’ve kept a list of what I’ve read. I recommend this habit to any serious reader. For one, it helps you get a realistic account of what can be read in a year. Second, I find that it gives me an intellectual auto-biography year to year. When I take stock at the end of the year I’m always surprised by how much I’ve learned from the hard work of others. Gratitude and humility are necessary components of intellectual life. Consider the following list an exercise in further ingraining these attitudes in myself. It contains several recommendations from what I’ve read this year. I was inspired to do this by David Watson over at the Kernel, whose list of recommendations for nuclear advocates can be read here.

Shorting the Grid by Meredith Angwin. Subscribers know that this book had a huge impact on me. As a layman, especially a layman without a technical background, Meredith’s book lucidly illuminated the fragilization of our grid and provided insight into an area that felt so opaque as to be more mere context. I have occasion to read it again in 2022 for research on a larger piece I’ve been commissioned to write. I look forward to spending more time with Meredith’s wisdom again as her book sent me down a whole new line of flight. Revisiting original inspirations always offers fresh insight.

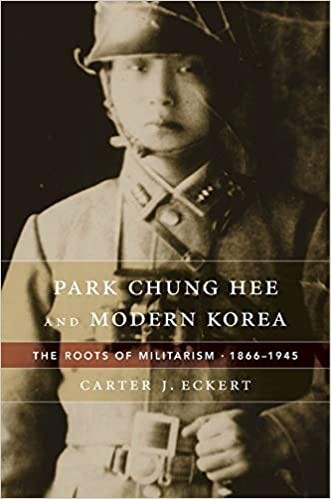

Park Chung Hee and Modern Korea: The Roots of Militarism, 1866–1945 by Carter J. Eckert. The Korean civil war has intrigued me since I was a boy. As a precocious kid with an abiding interest in combat, it was an American engagement about which little to nothing could be found. I spend some time this year redeeming my younger self’s desire to find out more about this event. Eckert’s book was supposed to serve as deeper background. Instead, it ended up the star of the few books I read on the topic. While it doesn’t offer explicit information on what Americans call the Korean War, it instead shows how Park’s time in an Imperial Japanese Academy in Manchuria shaped the man who would one day govern South Korea with an iron fist. The book masterfully elucidates how institutions shape human lives, the cultural contradictions of modernity, how the Japanese officer class saw their imperial mission, colonialism, militarism, and much, much more. I think of Park waking early to practice kendo by cutting at trees as a young man at the academy often. How have I been shaped by the institutions that, in part, reared me?

The Symposium by Plato (Bernadete/Bloom edition). I don’t know if we’ve ever escaped Plato or the questions his Socrates posed to interlocutors and to us. What I can say is that Bernadete’s helpful translation of The Symposium made for a more fruitful read of this dialogue than my last two go-arounds with it. This dialogue features several heavy-hitters in Athenian high society giving speeches on the topic of love. The party, at the end, gets crashed by the beautiful enfant terrible, Alcibiades. With Bernadete’s translation and Bloom’s exegesis entitled “The Ladder of Love,” we get insight into the difficult relationship between family, loyalty, love, and the state. This year, with the debates over CRT in the classroom, transitioning hormones for teenagers, and the basic questions of social solidarity the COVID crisis has inspired but have gone unanswered, this ancient text gives us much to think about—however we feel about these issues or Plato and Bloom’s thoughts on their fundamental aspects.

After Virtue by Alasdair MacIntyre. People have been telling me to read this book for a while. And because the force of those recommendations was so intense and because those who offer those forceful recommendations were so respected, I committed my other podcast, ex.haust, to reading through the entire thing. It ended up being one of the more intense intellectual experiences I’ve had. MacIntyre provides an account of why our society has fallen into acrimonious social coercion where no rational account of what we ought to do can win out over any other rational account. For believers in the Enlightenment, MacIntyre’s compelling case for the abandonment of the tradition of virtue as the source of our deadlock makes for a disquieting challenge. I cannot recommend this book enough. If you don’t have the time to read this (admittedly difficult) work of philosophy but want to know more, you can avail yourself of our reading series, which begins here and continues on Patreon.

A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations by Robert Bryce. I’m a Bryce fanboy, what can I say. This book is a fantastic crash course on the importance of electricity in the modern world. Robert’s got a great eye for a story and brings his subjects to life, which brings what could be a flat, academic topic to life. I should also recommend the accompanying documentary, The Juice, which has footage with many of the subjects covered in the book. I think this book is essential for anyone who wants to learn how to make the case for the vitality of electricity for prosperity. Run don’t walk to this one—and the movie, of course.

Play It As It Lays by Joan Didion. Every year I read something by Joan Didion. This year, a few months before her death earlier this month, I finally read her most well-known novel. I don’t know what took me so long to read it. Perhaps I was worried her fiction wouldn’t live up to nonfiction, which has indelibly shaped me as a writer and thinker. Well, this novel succeeded. Now that I live in LA, I can say that this book more than any other I’ve read captures its strange, weightless alienation. I don’t want to give away too much about this one. It can be read in a single weekend day, as she hoped for all her book-length work, and repays whatever time sunk into its reading as its read. Didion was a titan of the page and America was luckier than it knew to have her. Godspeed, Joan. Thank you for everything.

Energy: A Human History. This one has been staring me down from my bookcase for over a year. I haven’t read any of Rhodes’s books before. After reading this, I snatched up two of his works from used bookstores in New Mexico. He’s a fantastic writer and his ability to explain and dramatize technological development is, I think, unparalleled. If there’s a list of required reading for energy advocates, especially nuclear advocates, this should be on it.

The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe. I like sci-fi. In theory. Often, like a lot of so-called genre fictions, the quality of the prose (often poor) distracts from the world being built, the conceit explored, or the plot executed (often good). Gene Wolfe is a master stylist in the mold of one of my favorite authors, Jorge Luis Borges. This novel is the opening of a four-part series called The Book of the New Sun. It follows the life of Severian, an initiate exiled from the Guild of Torturers for visiting mercy upon one of their “guests,” as he makes his way through a dying world that hopes to see a new sun arrive to reheat it. Far from dystopian, though without any care for historical progressivism (exactly how I like it, in other words) Wolfe invites us to think about a world that has continued for so long its history has more to forget than to remember—and forgotten most of it is. This work is a rare science fiction where the past hangs more heavily over the action than the future. To showcase his style, I thought I might share its first paragraph, which manipulates time only the way a true prose craftsman can: “It is possible I already had some presentiment of my future. The locked and rusted gate that stood before us, with wisps of fog threading its spikes like mountain paths, remains in my mind now as a symbol of my exile. That is why I have begun this account of it with the aftermath of our swim, in which I, the torturer’s apprentice Severian, had so nearly drowned.”

Until next year!

These all sound good. I will brag that I got my copy of The Shadow of the Torturer autographed by Gene Wolfe many years ago.