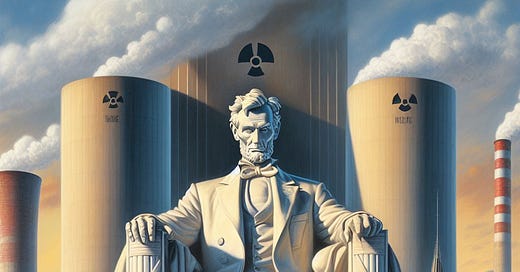

A Republic of Industrial Cathedrals

For an atomic America of the people, by the people, and for the people

Nearly three years ago,

called me. She was headed to Buchanan, New York, the Indian Point nuclear power plant’s host community. The plant was set to close, and she was to attend a commemoration ceremony for its final day of operation. Speeches were to be given. Madi had never written a speech for an occasion like this and she wanted to know if I could help her. Of course, I had never written something like that either. But I said I would take a swing at it.I spent most of the next day staring at the map of the United States that hung over my desk. I would start writing; then I would read what I’d written; then I would hate what I’d written, so I would delete it. Then I would gaze back up at America, sigh, and begin again. Eventually, I saw what was wrong: I needed a template. The whiteness of the page had foundered the vessel of my thought as so much water pouring into small skiff. If I had something to orient me, I might could pull it off. But if I needed a template, then I had to know what kind of speech I was supposed to write.

It dawned on me: the ceremony was a funeral for Indian Point; this speech was a funeral oration. I cracked open my copy of Thucydides. Who better to help me than Pericles and his stirring speech for the Athenian dead felled on the field of honor? But Pericles’ speech somehow turns into a victory speech, a paean to Athenian excellence. How could we feel victorious about the loss of Indian Point? Especially when the Diablo Canyon, Byron, Dresden and Palisades nuclear plants still lay bare-necked on the chopping block, waiting for the axe to fall.

So, I put away The Peloponnesian War and looked back up at America. I pondered the shape of New York. If Pericles couldn’t help me, who could? My eyes drifted down to Pennsylvania, where a small cluster of men had hammered out the Articles of Confederation, their hearts trepidatious as they readied for war against the greatest power in the world. And where, two days before the Fourth of July, Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain of the 20th Maine found his company depleted of men and ammunition at the summit of Little Round Top as wave after wave of Confederates charged his position, hoping to flank the whole Union Army. Desperate, he steeled himself and screamed for his men to fix their bayonets and charge. Against all odds, Chamberlain and his men repulsed their attackers—Gettysburg.

And then, I thought: Lincoln. Like so many Americans before me, I turned to the Great Emancipator for counsel. I premised the first version of Madi’s speech after his sober, solemn, brief “Gettysburg Address.”1 In writing the speech, I meditated on what it would mean to lose Indian Point, what it would cost Buchanan and those who lived there—and what that meant for the country. Two weeks later, because I had spent time in communion with Mr. Lincoln, contemplating the loss of Indian Point, I wrote a piece for The American Conservative, “Nuclear Power Plants: Our Industrial Cathedrals.”

Rereading it now, I see that it contains the seeds of the questions—political, historical, philosophical—that have consumed me since.

, in his new docu-series, Juice: Politics, Power and the Grid, gives my idea of industrial cathedrals a flattering place of pride. He and his collaborator Tyson Culver graciously titled the series’ conclusion with the phrase. And given that more people will now be introduced to the idea, I thought I might update it with some of the thinking I’ve done since.I. Why Cathedrals?

As I mention in Robert’s documentary, the idea of comparing nuclear power plants to cathedrals came to me when Notre Dame caught fire several years ago. I began to think about what it took to accomplish that civilizational jewel. But more than that, I considered the generational succession of artisanal and architectural jobs Notre Dame’s construction provided. The time frame to achieve its excellence seemed to me an antidote to the presentism that dominates our lives.

But nuclear power plants are like cathedrals in another way: for most of Christendom, communities were built around their churches and cathedrals. Likewise, NPPs become the economic hub around which their communities are built, bringing wealth and enriching civil society. And as Madi Hilly always tells me, “The only thing the Simpsons got right about nuclear is that Homer could own his own home and provide for his family on a single income without a college degree thanks to his job at the plant.” We can also make this point in the negative: communities that lose their NPPs never recover.

And then there’s nuclear’s potentially immortal lifespan. A nuclear plant properly maintained can survive for at least a century and likely much longer. That means that someone who helps build a nuclear plant can rest assured that successive generations of their progeny can work there, providing cheap, clean electricity to their area.

All this is why I called nuclear power plants America’s Industrial Cathedrals. But what does it mean to inherit these cathedrals? And what will it mean to build more? And why should we do so in the first place?

II. Our Patrimony

Everything we have today had to be achieved. Our forebears brought it forth onto this earth by the work of their hands and in the sweat of their faces. We can respond to these salutary achievements in a variety of ways, two chief among them: indifference or gratitude. The first is common to us all, because it usually stems from ignorance (which I mean in the strict and non-pejorative sense). In our ignorance, indifference to these achievements leads us to take for granted our wealth and liberty.

Gratitude, on the other hand, impresses upon us the sediments of time. Later in life, John Adams spent much of his time in correspondence with curious citizens who wanted to know more about the founding, which by then had already ascended to exalted memory. Adams did his best to discourage inquirers from their habit of mythologizing the revolutionary era as some golden moment of patriotic political harmony that rang out the world over.

“Every measure of Congress from 1774 to 1787, inclusively, was disputed with acrimony and decided by as small majorities as any question is decided these days,” he wrote to one correspondent. To another, he described his frame of mind as he and his peers signed their names to the Declaration of Independence. “I could not see their hearts,” wrote Adams, “but as far as I could penetrate the intricate foldings of their souls, I then believed, and have not since altered my opinion, that there were several who signed with regret and several others with many doubts and much lukewarmness.”2 Adams’ words counsel against nostalgia, which denigrates the past by ignoring its contingency, narrow margins, and great risks. We can take none of what we have for granted.

Lincoln offered a related lesson: he opens the address by measuring the time between the country’s founding and the day of his oration—and he does so in English measures to emphasize the link to our provenance. “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” Proposition can be read doubly: first in the strict, geometric sense. Our equality is written syllogistically in the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Memory is begotten by gratitude, which in turn begets a sense of patrimony.

The second reading of “proposition” is more common: a wager. Taken together, we can see that in Gettysburg’s dark shadow and in the midst of “a great civil war” we were “testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.” Lincoln hoped that in our deeds such a nation “of the people, by the people, for the people” would not “perish from the earth.”

After Gettysburg, the prospect of the proposition’s endurance seemed doubtful. Fifty-one thousand Americans were killed or wounded in that three-day battle alone (for reference, 58,000 Americans were killed or wounded in the two decade war in Vietnam). The body count from Gettysburg was so shocking that, in the aftermath of that Union victory, New Yorkers rioted against the draft—a dozen black Americans were lynched, while hundreds of others fled the city. All told, 120 civilians were killed, 2,000 were injured, and 50 buildings were burnt to the ground in the rioting. Lincoln had to divert part of the Union Army from hounding General Robert E. Lee to restore order in New York City, a 200-mile march north.3

So, Lincoln called on our memory of the founding to help us see the preciousness of our proposition so that we might remain steadfast in our maintenance of it, even in the midst of mutual violence and acrimony. Here we have what Christopher Lasch would emphasize over a century later as the distinction between nostalgia and memory. Whereas nostalgia “obscures the connections between the present and the past,” memory preserves and clarifies them.4 Memory is begotten by gratitude, which in turn begets a sense of patrimony. We grasp this even in the structure of the Gettysburg Address. The first paragraph begins in the past, the second in the present, and its conclusion turns toward the future.

I am suggesting our industrial commons—in particular the power grid and especially its nuclear power plants—can be seen, like our Declaration and Constitution, as our patrimony. As our founding documents constitute the fabric of our political and social lives and underwrite the security of our rights, the grid enables the sum total of our activities. The grid is, as Dr. Chris Keefer calls it, the “mother network” of our society. And it is a commons; a tapestry of infrastructure and institutions that comprise the largest machine on earth. We inherit the grid and we must conserve it so that it may be passed on to our posterity so that they may make use of the wealth it provides. And there is no such thing as a wealthy society with a weak electrical grid.

III. An Atomic Republic

Lincoln stated that neither he nor anyone else could consecrate the ground of Gettysburg because so many men had already hallowed it by giving “the last full measure of their devotion.” But he goes a step further: “The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.”5 What could Lincoln’s words, anyone’s words, compare to the sacrifice of these men? Implied here is a call for less talking and more doing.

But do what? And for what? “It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced,” Lincoln continued. For those among the audience, that work was to guarantee the preservation of the Union and “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.” This burden falls unevenly on each succeeding generation. Blessed we are that we do not have to make a stand on Little Round Top. Our task—one of our tasks—is to tend to our industrial commons. But tending to the industrial commons is not a question of how we ought to ration its fruits, but how it can be grown to provide more amply and in perpetuity. The power density, reliability, cleanliness, and potential immortality of nuclear makes it the perfect vehicle for discharging our duty.

The politics of climatism make this impossible. In fact, climate policy is already fraying our industrial commons apart thanks largely to its preferred energy policies.6 Yet the problem facing our industrial commons is not simply a question of technology. Climatism and its adherents didn’t just bet on the wrong horses—wind, solar, and batteries—but continue to promote an outlook that decouples us from the past and the future, trapping us into a panicked presentism that manifests in poor policy choices and deforms our sense of belonging. This was achieved with an almost syllogistic economy of rhetoric: the climate crisis will kill us all; we brought this doom about via our past industrial achievements; we must forsake the past to survive and rework the entire of industrial society; but any interrogation of the potential consequences of such a reworking, i.e. any real regard for the future, is forbidden. We simply do not have time to think our way through climate crisis, they tell us. We must act now. Any dissension is labeled “denial” and should be banned from the public square. Such a logic proves lethal to any sense of patrimony, as it harangues us with the same question over and over again: what won’t we sacrifice to save ourselves?

I no longer find the climate-oriented view of energy policy viable for stewarding our industrial commons. I want to move beyond climatism and environmentalism as the prisms through which we view energy and industry. Why should we feel ashamed for the achievements of our civilization and all the sacrifice they demanded? Why should we surrender the patrimony of our Declaration and natural rights to ecology, as many environmentalists have called for? It is all so much blackmail, a cross between delusion and sabotage. No, the truth is nearer to Lincoln’s reckoning: “All creation is a mine, and every man, a miner.” And I refuse to believe our nation is unworthy of the full measure of our devotion.

We need a new vision, one that anchors us in the past, guides us through our present, and opens into our future. The Industrial Cathedral is the lodestar of this vision. Picture the Mark Twain Mississippi Reactor Corridor, the Frederick Douglass Institute for Atomic Excellence, the Gettysburg Reactor Park. Picture, if you will, an America that has had nuclear power for longer than it hasn’t; a Republic of Industrial Cathedrals of the people, by the people, and for the people that shall not perish from the earth.

Though, as Gary wills and others have noted, striking parallels exist between Lincoln’s speech and that of Pericles. Also, Madi made her own alterations to the Indian Point speech, naturally, but you can read it here.

These quotes from Adams’ letters were taken from this lecture given by the historian Joanne B. Freeman. The entire Adams family has much of their correspondence cataloged online, but I had not the time to hunt down the exact citations.

Diana Schaub, His Greatest Speeches: How Lincoln Moved the Nation (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2021), 64.

Christopher Lasch, The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company: 1991), 14.

The irony here exists only in hindsight. Lincoln could not have known his words would become forever welded to the events at Gettysburg. And it’s worth noting a 2-hour speech given by Harvard president, Gerard Everett, preceded Lincoln’s—who remembers that?

You do not have to take my word or his word for it, of course. But you can take the word of the North American Electric Reliability Corp. Or the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. In their testimony before the Senate last year, every member agreed we face an unprecedented reliability crisis. “The United States is heading for a very catastrophic situation in terms of reliability,” Christie told the Senate last May. “The arithmetic doesn’t work…This problem is coming. It’s coming quickly. The red lights are flashing.”

Damn this is good. And not just because Emmet mentions me or our new docuseries. (Although I do not object to that.)

I love this section and really wish I written it:

I no longer find the climate-oriented view of energy policy viable for stewarding our industrial commons. I want to move beyond climatism and environmentalism as the prisms through which we view energy and industry. Why should we feel ashamed for the achievements of our civilization and all the sacrifice they demanded? Why should we surrender the patrimony of our Declaration and natural rights to ecology, as many environmentalists have called for?

It is all so much blackmail, a cross between delusion and sabotage.

Preach it, Emmet. Preach.

"it harangues us with the same question over and over again: what won’t we sacrifice to save ourselves?"

And we won't even save ourselves. The prescribed cure is worse than the disease.